Blog

Poor API Design, not Security, was at the core of the Cambridge Analytica scandal

Note: This story has been cross-posted to my LinkedIn page.

In the wake of the outrage against Facebook with regards to the data accessibility of mass users on their platform by actors such as Cambridge Analytica, the company has been insisting that it had not broken any laws. And it was right. Users signing up to Facebook for the first time (as early as a decade ago), gave consent to the use and sharing of their data, oblivious at the time to the extent to which data collection techniques would evolve in the coming years, and how lucrative the digital advertisement industry would become.

While I’m not qualified enough to comment on the legal aspects of the T&Cs, nor do I want to get into GDPR, one thing about this whole saga has been sticking out like a sore thumb: the notion that this was a data breach, or that Facebook and Cambridge Analytica were in cahoots with each other. Very few reports actually outlined the issue for what it was:** a really, really poor and dangerous API Design on Facebook’s side.** Cambridge Analytica did harvest and gather the data of millions of American voters, and whatever your thoughts on the ethics of data harvesting may be, it is still important to distinguish that they didn’t have to break into Facebook’s walled gardens to get this information. Facebook provided them, as well as any other developer, with the tools, documentation and examples on how best to consume these APIs. Most coverage about this saga was sensationalized as a data breach or an unauthorised intrusion — even Facebook was acting as if this were an isolated incident which they are now rectifying. It’s not. It was their willful exposing of this information which tons of apps had access to, not just CA. Instead of a hack, we should be reporting this as a massively poor design decision by a company which was reckless enough to allow developers access to such fine grain user data.

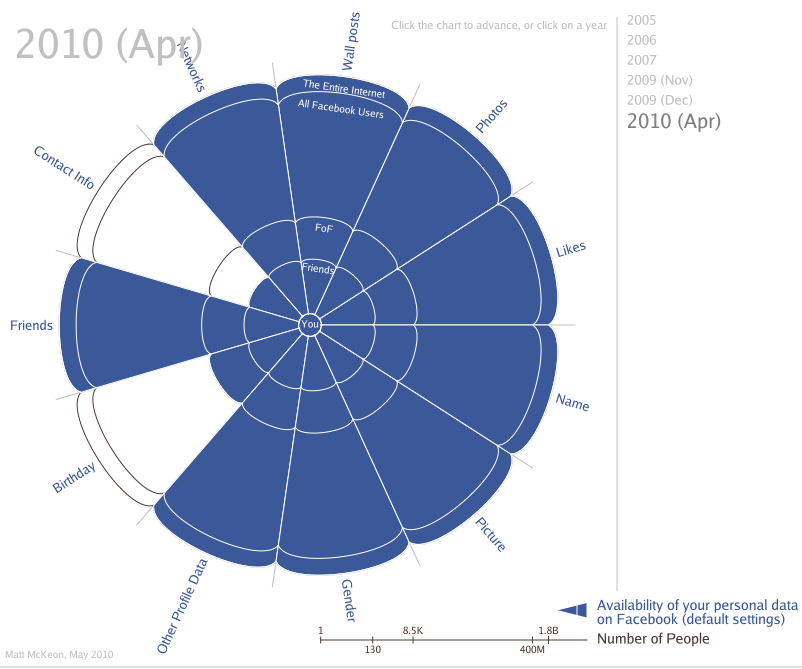

Matt McKeon, a developer with the Visual Communication Lab at IBM Research’s Center for Social Software, did some analysis a few years ago on how the default privacy settings on Facebook changed between 2005 - 2010. Personal information went from early on only being shared with your friends, to then with the friends of your friends, and so on. The type of information being shared grew as well — and all of this was made available to any developer who allowed social login on their app or website in the early years of Facebook’s Graph API. Version 1.0 of the Graph API was in use from **2010 **and finally deprecated completely in **2015. **There’s an incredible write-up on the Graph API and how it brought about this revolution in large-scale data provision by Jonathan Albright that I recommend you read.

Note that this chart is from 2010. This is **before **data sets such as location information and body sensors were readily available in smartphones. An updated version of this chart taking into account machine learning capabilities with things like facial recognition would be terrifying.

The data economy is only just getting started, and we’re very much in a world where our every interaction with technology is digital breadcrumbs for someone to derive psychometric insights from. You have situations like the one last year — where the CEO of Roomba publicly stated that they “could reach a deal to sell its maps to one or more of the Big Three [Amazon, Apple, Google] in the next couple of years.”

Big Data — at its worst, is the evolution of telemarketing, only infinitely scarier and intrusive.

IoT and Big Data will be driven by APIs, and even though they will enable some incredible use-cases, products, and services — there’s serious design decisions that need to be taken into account when exposing your data to third parties. Especially when applying a one size fits all model as Facebook did with the first version of Open Graph, giving any application the potential to utilize tons of information that they didn’t need. Remember Farmville? Well, its parent company, Zynga had access to millions of more Facebook accounts than Cambridge Analytica because the underlying API was exposing far too much information.

So, while every sector is hungry to get involved in the data economy and exploring the possibilities of selling and exchanging data assets, this is a timely reminder that API design should not be at the expense of user privacy.